496 pages.

First published March 5, 2024 (Penguin)

Non-fiction.

In 1989, James Kaplan, through a happy “coincidence”, found himself at Essex House in New York, interviewing Miles Davis for Vanity Fair:

It was an assignment I’d lucked into through my magazine-editor brother, who knew a Vanity Fair editor who’d said he needed a profile of Miles to accompany an excerpt from the trumpet legend’s forthcoming memoir…

Kaplan doesn’t think he did very well then: he didn’t know enough to ask Miles the right questions, and the initial two hours just weren’t enough anyway:

I asked timorously if I might have some more time, and Miles rasped, “Come back tomorrow.”

Of course I returned the next day, without the publicist this time, and the second session went much like the first, full of Miles’s sentence fragments about tangential topics; further discussion about his artwork; stories about matters and people I hadn’t the wherewithal to understand; and minimalist, wandering answers to my jazz questions. At the time I had the sinking feeling that I would draw little of substance from him, even over the course of three hours…

Jazz greats Miles, Coltrane and Bill Evans are the subject of this immersive history—probably the only book you’ll ever have to read on them. Not being more than an occasional fan of jazz, I have, though, of course listened to Miles and Coltrane (endlessly, even), but I had never heard of Bill Evans, the bespectacled white piano man who looked, in his youth, like a teacher, and who, along with Coltrane, became a favourite of Miles’s. Kaplan traces the careers of all three (with cameos from just about every major figure of jazz, through interviews and whenever their paths crossed with those of the three subjects).

Jazz was “feared and reviled” by white society at the beginning of the twentieth century, but rose to become, by the middle of the century, the definitive American sound (although it was quickly overtaken by rock and roll by the 1960s). These three men were instrumental in this, working hard on their craft—practising obsessively, playing perhaps thousands of gigs between them, going on the road—and unfortunately ruining their lives and health in the process. Because, as Kaplan shows, the story of jazz greats is also the story of chaotic personal lives, and also heroin (mentioned 116 times in the book), cocaine, alcohol, and marijuana:

Heroin and alcohol incapacitated merely terrestrial musicians; Bird could be jostled awake from a drug or whiskey stupor and start playing brilliantly, instantly.

“I heard Charlie Parker and that was it,” Red Rodney said. When you’re very young and immature and you have a hero like Charlie Parker was to me, an idol who proves himself every time, who proves greatness and genius. . . . When I listened to that genius night after night, being young and immature and not an educated person, I must have thought, “If I crossed over that line, with drugs, could I play like that?” “You want a sense of belonging,” Rodney said. “You want to be like the others. . . . Heroin was our badge. It was the thing that gave us membership in a unique club, and for this membership we gave up everything else in the world. Every ambition. Every desire. Everything. It ruined most people.”

Dizzy liked to take a drink and enjoyed marijuana, but never used heroin, at least intentionally. (He once snorted some, thinking it was cocaine, and instantly passed out.)

“I think for Bill, the white guy from Plainfield, New Jersey, who looked every bit the part of the white guy from Plainfield, New Jersey, he really felt that to get into that world he needed to become a junkie,” the drummer Eliot Zigmund, who played in Evans’s trio in the seventies, told me. “And boy, did he become a junkie.”

Coltrane, the super intense, spiritual man, also fell into using:

In all the hundreds of pages of interviews in Coltrane on Coltrane, Coltrane himself makes no reference to his drug use—although apparently he did speak candidly in 1960 to the Swedish journalist Björn Fremer about his addictions to alcohol and narcotics, and his “deep regret that he’d wasted so many years of his life because of them”—but then asked Fremer to remove that part of the interview from the article.

Miles was apparently so upset with Coltrane over his habit that he hit him, and fired him; Coltrane later went to work with Theolonius Monk, kicked his heroin habit, and “had a spiritual awakening” that led to that transcendental experience, A Love Supreme:

“During the year 1957,” he would write in the liner notes of his great 1964 album A Love Supreme, I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life. At that time, in gratitude, I humbly asked to be given the means and privilege to make others happy through music. I feel this has been granted through His grace.”

The pressures were everywhere. “I started using around 1945 when just about all the big names were,” [Dexter] Gordon told an interviewer years later. Bird. Sonny Stitt. Bud Powell. Fats Navarro. Gene Ammons. Billie Holiday. And white musicians, like Stan Getz, Gerry Mulligan, Red Rodney, Chet Baker. In his memoir, Miles speaks of the younger musicians who became heavy users in the mid- to late 1940s, starting with Gordon and also including Tadd Dameron, Art Blakey, J. J. Johnson, Sonny Rollins, Jackie McLean. And himself.

But Miles managed to kick his heroin habit—eventually (although he continued taking cocaine), and went on to have a second life, marrying Cicely Tyson in 1981, and coming back to music in 1980 after a six-year break for health reasons.

Coltrane died at 40 of liver cancer. Evans died at 52, never having conquered his demons, and, like Miles, having traded heroin for cocaine. Miles died in 1991, aged 65, after a lifetime of health struggles, and in the end, a stroke.

I don’t know if this will be Kaplan’s magnum opus, but it will surely come close. It’s a brilliant book for jazz and music lovers, but is also an astonishing historical record of, particularly, Black musicians (and Bill Evans): their rise, peak, and personal fall, although in the case of the three musical luminaries of this book—Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Bill Evans, one must argue that they never fell, although they died. They will live forever; this book becomes part of the reason.

Miles: “Man, sometimes it takes you a long time to sound like yourself.”

Many thanks to Penguin and to NetGalley for early access.

Support independent bookshops and my writing by ordering it from Bookshop here.

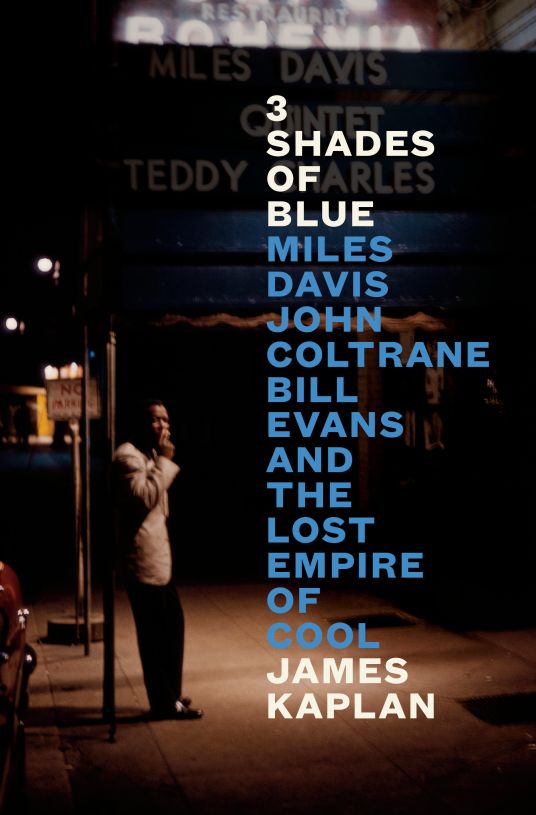

One thought on “3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans and the Lost Empire of Cool x James Kaplan (DRC)”